Insights from Rev. Grisom on Black Love, bell hooks and Beyond

Reverend Ebony Grisom–also known as Rev G, is Georgetown’s Interim Director for Protestant Ministry. She describes herself as a Black woman, New Yorker, and Christian. Fun and funny. At 3700 O St where “faith is in the air” she dons a collar. Off-campus faith is just as salient to her but she’s often “undercover clergy.” [Note: This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.]

How do you think faith and love come together?

There is no greater love. I experience my faith in the Triune God. I believe the Bible is my whole, my holy writ. If I would stick with ‘God as love’, that’s it. It’s as simple and as complicated as that. For me, faith is an anchor, the only reason I can believe that it’s possible.

Now, sometimes I think we confuse love for sentimentality. It’s not just rainbows and unicorns. Love is also about accountability. Love is also a stern resilience. Love is also radical honesty. You know, sometimes love tastes like Robitussin, right? Not always Skittles. And so sometimes we miss it, I think because we’re expecting a saccharine sweetness. And I say saccharin with intentionality because saccharine is artificial. Often we miss it because we’re chasing the artificial sweetness, the artificial high.

At this moment, I’m even thinking about a shot, like a vaccine, antibiotic, or steroid. Imagine taking medication in the form of a shot. On contact, it hurts. But later, we feel better. Our ailment is, we are, closer to healing with every shot. Love can be that way if we allow it.

In the preface of all about love, bell hooks wrote, “I feel our nation’s turning away from love. I write of love to bear witness both to the danger in this movement, and to call for a return to love.” Do you feel our nation is turning away from love?

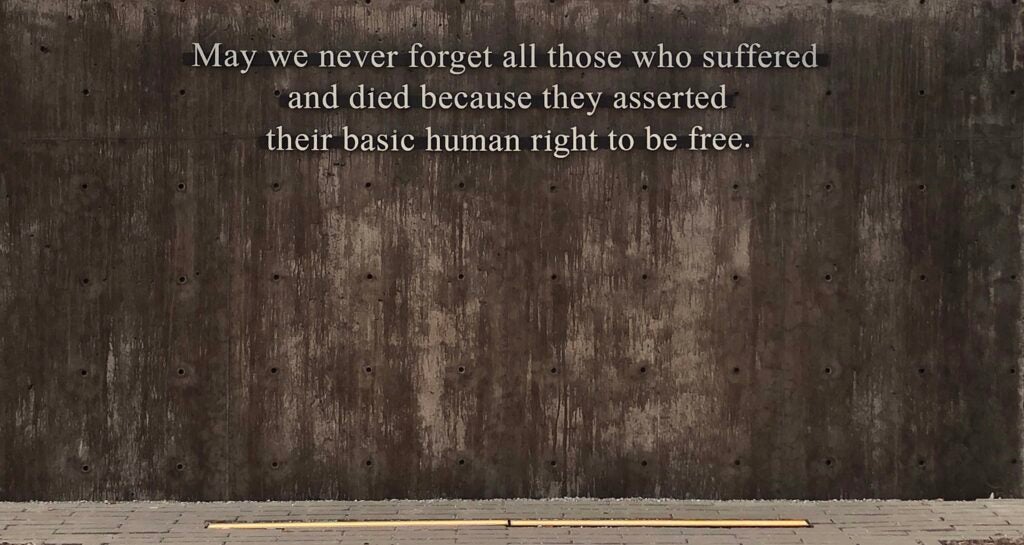

I’m not sure that we ever were loving as a nation. This is top of mind right now as I just came back from the Civil Rights Immersion Alternative Break Program (ABP). The rancor, animus, and violent beginnings of our nation. Who did we love? As a country? What do we love besides our own self? And likeness? What do we love besides whiteness?

For sure I expect struggle–just being a Black woman. But there is a type of Christianity that says, “you know, it’s a shame, what’s happening down here”, and “oh, you poor Blacks” or “oh you poor ‘whomever’, sorry, you were born a woman, but when you get to heaven, it’ll be better by and by.”

When I say ‘my struggle’, I’m remembering the Lord’s Prayer, “thy Kingdom comes, thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven” [Matthew 6: 10]. I see that as us, starting with myself, reaching up to heaven to pull it down to earth. I interpret that to mean God wants us to have the same kind of abundance on earth as it is in heaven. What do I hope for? I expect that Heaven will be–first of all, I pray that I make it–but that it’s gonna be great and wonderful. Streets paved with gold. I’ll get to see my great-grandmother and all the folk. All the people I love and the people who love me.

And yet, “If Jesus has come, that I might have life and have it more abundantly [John 10:10].” That means I don’t have to wait until I get to heaven. So alright, I’ll march, or protest, or vote, or challenge. We talk about the “Spirit of Georgetown”: contemplation in action and a faith that does justice. That’s active–even contemplation is active. But that’s not silos, right? That is a full integration: of life, of being, of humanity, of love.

In 2020, were people having a spiritual awakening alongside or with the development of a racial or political consciousness?

I will put it a slightly different way: people became willing to see that faith is political. Love is political. In the sense of politics being about the polis, the people, there’s no way to engage any aspect of life with integrity, without thinking politically. Especially in 2020, more people started to see [political] engagement as an integral part of their whole life. I have been part of faith communities that see faith in a silo, which is near but separate from family, which is near but separate from work, which is near but separate for whom I’m voting. All these things may be on the same block or on the same acre, but sometimes we don’t see them as connected. And [in 2020] that was really hard to do–not only because of the pandemic but because of the increased racial animus. It was impossible to ignore.

You mentioned our tendency to see things in silos. What do you make of the way that bell hooks represents the intersectionality of human experiences?

bell hook’s salvation convicted me of the ways I have been formed to separate aspects of my being…how antithetical that is to our humanity. It’s helped me to embrace and stretch–almost like putting on a glove and making sure my fingers get all the way to the tip and letting it fit–being a loving being in every sense of the word, unabashedly. Very often, especially in sort of fundamental, evangelical Christianity, there’s ‘you can love but only like this.’ And I experienced salvation, no pun intended, as a call to a holistic embodiment.

It doesn’t make sense to talk all about love in a sermonic moment, but not at home or in your office. To talk about the love of Christ, but still turn water hoses on people. Talk about the love of Christ, but not want people to have health care or a living wage. When you recognize cura personalis–this inseparability of mind, body, spirit. it becomes clearer to see the hypocrisy and to be disenchanted with this sort of segmented spirituality.

This is what we as a country struggled with in the wake of Brown v. Board of Education. On the ABP trip, we were in Montgomery at the Rosa Parks Museum, thinking anew about the Bus Boycott. One of the exhibits talked about how initially boycotters weren’t even fighting for desegregation. They just wanted more humane treatment and respect in segregation. In a way, thank God that the segregationists were so entrenched and so racist because that’s actually what built the boycotters’ resolve. As if to say, they’re not going to give us that so let’s take it all. That’s certainly what it means to be Black in America. Oh, I can’t sit at the table? Give me the whole room.

Sometimes it feels like there isn’t even a willingness to compromise or concede to another’s humanity. And I experience that as the Incredible Heartbreak. My favorite scripture, Romans 8:28—All things work together for those who love Him and are called according to His purpose. That made them rise up and demand. So I’m glad y’all wouldn’t treat them with respect because that made them rise up and demand it all.

This is the second installation in the Blackness & Faith series by Kawther Berhanu (C ‘19, MSFS ‘22).

Photos in this interview were provided by Rev. Ebony Grisom