Bongiwe Bongwe Talks about Faith, Trust and the Many Ingredients of Love

Bongiwe Bongwe (MSFS’22) is an eldest sister and a Black South African who has been studying in the US since 2016. At MSFS, she is concentrating on Global Business and recently spearheaded the 2022 Georgetown Africa Business Conference. She describes herself as “a person trying to make the most of her time on this earth.”

bell hooks wrote “there can be no love without justice” and “the heart of justice is truth-telling.” How do you see the connection between faith, truth, and justice?

At a macro level, how do you engage in forgiveness? When I think of truth-telling I always think about the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission. At the time, many families wanted people to know what had happened to their relatives. It was going to be painful, but at least everyone would know the truth and have a shared understanding of what happened under apartheid. On the other hand, some families actually wanted action–change or consequences. That has created a lot of tension that persists today. People look back at our history and ask, did we just act like everything’s okay, and not really deal with the root issue? In my younger years, I thought justice was simply the acknowledgment of wrongdoing. Now, I think, it means accountability: how do we take action to right an actual wrong?

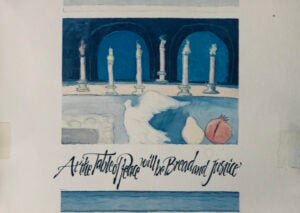

My dad loves the phrase: “At the table of peace will be bread and justice.” I don’t know if the quote has religious origins (my dad got it from a painting he bought at a store – see the image below), but in a way, I think that speaks to its power. It’s always stuck with my understanding of a universal spirituality. No matter what religion you follow, that quote will resonate because we have all experienced and witnessed the way in which injustice leaves people in such impoverished situations. I find that justice conversations in South Africa and in the US, rightfully keep coming back to how people have deliberately been excluded from an equitable share of resources. Justice can also be monetary. I think the discussion of reparations is one we have shied away from because there is the sense that all we care about is money. But we are entitled to a lot of things because Black people built this country and continue to play a huge role in the benefits people reap. The lack of economic justice has had financial consequences; justice has to have a component of giving people back that bread.

How would you describe your spiritual community?

I went to an Episcopalian boarding school. We had to go to chapel twice a week and sing hymns. When I came to the US, that stopped and I had to find what religion means to me as opposed to sort of having it imposed. That shift dramatically changed my understanding of spirituality. Today, when I think of the values that make me who I am, spirituality feels the most personal. Now, I definitely think my spirituality is more rooted in sound. I started to notice that the way I actually channeled that best was through music. I have an extensive playlist of Gospel songs and spiritual music. It helps the most when I need a little more centering and calmness. I listen and spend time outdoors. Something about being outside with fresh air gives me the feeling that I can release and think through things.

Also, it sounds very millennial, but spiritual podcasts have really helped me. Before the pandemic, I wasn’t a big fan of the podcasts, but I moved to DC right before COVID, and that was the first time I was really alone. For the first six months, I literally spent 95 percent of the time by myself. Everybody that I would try to call in South Africa was sleeping because of the time difference. I needed to find ways to fill up my lonely space with some kind of interaction and feeling; podcasts gave me that space. They have reminded me that I’m not alone. I think that’s the whole point of spirituality; it gives us a sense of comfort and connection. Hearing other people’s stories and how they are healing through different things allows me to heal as well.

bell hooks says only love can heal the wounds of the past through committed loving relationships. In relationships, are we able to see ourselves with new eyes and can it be spiritual?

In a podcast episode of Black Girls Heal, they talked about how often firstborn Black and immigrant girls are ‘parentified’. We deal with a lot of pressure and become very afraid of disappointing people, which then turns into love avoidance. So when we are met with love from someone who does not expect these same things of you: to pay for everything or have it all sorted, it feels weird. We want to run away. That makes me think about religion. I’ve never quite been able to come to terms with the fact that religion is supposed to be a space where you love, no matter what, and then having somebody return that love flaws and all? It helps you be less love-avoidant.

There is something spiritual about making a choice to trust someone and to open yourself up–especially if you have been hurt before. For the first time in a long time, I’m in a very healthy romantic relationship. Something that my boyfriend has taught me is that you just need to talk. You actually just need to get it out and say it in order to work through it. You discover things that bother or affect your inner child that you didn’t even know were there. It comes out. I tend to harbor things. I don’t want to grow old and have aches just because I kept so much in. I’m trying to cleanse my heart, to process things, heal and refresh, learning to let go which comes with forgiveness.

It’s also about communication, especially how you actually listen and understand. If we don’t communicate honestly and openly, then the inverse means closed and hidden. Just being able to speak and let things out is the first step. I think that’s rooted in spirituality. Every religion has its own way of helping you let things out–through speaking or praying or confessing. It’s built-in. But it’s still hard to actually do that. That’s a persistent practice.

In all about love, bell hooks describes love as having several ingredients: “care, affection, recognition, respect, commitment, trust and open, honest communication.” Would you like to comment on any of the ingredients? Anything else that you would add?

She knew the recipe. There’s something about ‘recognition’ that I think is distinct from ‘respect’. I would describe recognition as I see you and all the different elements that make you who you are today and respect as ‘I then carry a level of understanding and regard for the fact that you are this person’. When we talk about diversity, sometimes people miss that you can recognize diversity, but not necessarily respect differences. On campus, we do a lot of recognition work, but I think to institutionalize it is to respect it. Having consistent books and essays in our classes that reflect diversity over the years, means more to me than just one special DEI (Diversity, Equity and Inclusion) event. The syllabus outlives us all. I really like that bell hooks said “care” and “trust”, because the more you trust someone or something or an institution, the more you care about it. I think I would add “intentionality” to this list.

This interview is part of the Blackness & Faith series by Kawther Berhanu (C ‘19, MSFS ‘22).

Photos courtesy of Bongiwe Bongwe (MSFS’22).