Love: A Commitment to Healthy Conflict and Spiritual Growth

Jerome Smalls (MSB ‘19, G‘23) identifies as a Black Southern man and describes himself as both student and educator–newly privileged with educational, social, and financial capital. Music has been a formative influence on his journey of faith and love–especially Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly and Mick Jenkins’ THC (The Healing Component).

For Jerome, developing language, community, and practice around love and spirituality have helped him gain clarity and confidence about who he is and equipped him with the tools to engage others. He published his coming of age story, Small Talk: One Youth. Seven Stories. Countless Lessons. Jerome now works at The Hub for Equity and Innovation and is pursuing a Master of Arts in Educational Transformation at Georgetown.

How were you introduced to bell hooks? How have her teachings shaped your time at Georgetown?

My former professor, Dr. Sylvia Onder, gifted me hooks’ book, all about love for Christmas; it’s taken two years to read it with justice. In Mick Jenkins’ song Angles, Jenkins writes, “I had to get to know myself before I could claim I love me.” That’s what I hear from bell hooks. She describes love as a collective commitment. It’s a leap of faith to invest in each other’s spiritual growth. It’s not a commitment to physical growth, accolades, or material growth, nor is it tied up in romantic or lustful desires or familial obligation. I recently watched a Master Class series on “Black History, Black Freedom & Black Love.” They talked about how the antithesis of white supremacy is Black Love.

How is Black Love popularly, and colloquially conceived in pop culture? How does it mirror or depart from the assertion that Black Love is the antithesis of white supremacy?

I have a couple homies I can talk to about these topics, but most folks are Black women. It’s easier to talk with Black women because they have deeply explored and interrogated love and have an inherent openness to tenderness. With most heterosexual Black men, even this notion of tenderness is taboo–maybe with the exception of a Black father showing tenderness to their child. These are nuanced conversations that a lot of brothers my age haven’t grappled with or aren’t willing to grapple with. So when I find other guys who are willing to engage, and especially if they’re also Black and from FGLI (First Generation, Lower-Income) backgrounds, I gravitate towards them.

The problem is Black Love gets reduced to this commercialized, heterosexual idea of who should be loving each other. Love & Basketball, Love Jones. But that’s actually, only a sliver of the vast universe of Black Love. Love isn’t butterflies in the stomach when a cute girl smiles at you. Love transcends physical attraction. Like bell hooks said love is a commitment to one’s spiritual growth–point blank period. Love is love–with your romantic partner, children, parents, and friends. The only difference is the context of that relationship. When you have that perspective, love becomes a tool of accountability to call-in folks when they’re moving in unloving ways like perpetuating homophobia and colorism.

You’ve described the experience of evolving towards our authentic selves. What does homegoing look like with new eyes?

I realized I was very naïve in my thinking about race relations in Charleston. It took a lot of unpacking and learning to understand that just because Black and white folks coexist doesn’t mean that there’s healthy peace. Being who I am now, in all settings, may cause healthy conflict and I’ve recognized that isn’t something to shy away from. Discomfort is a growth opportunity.

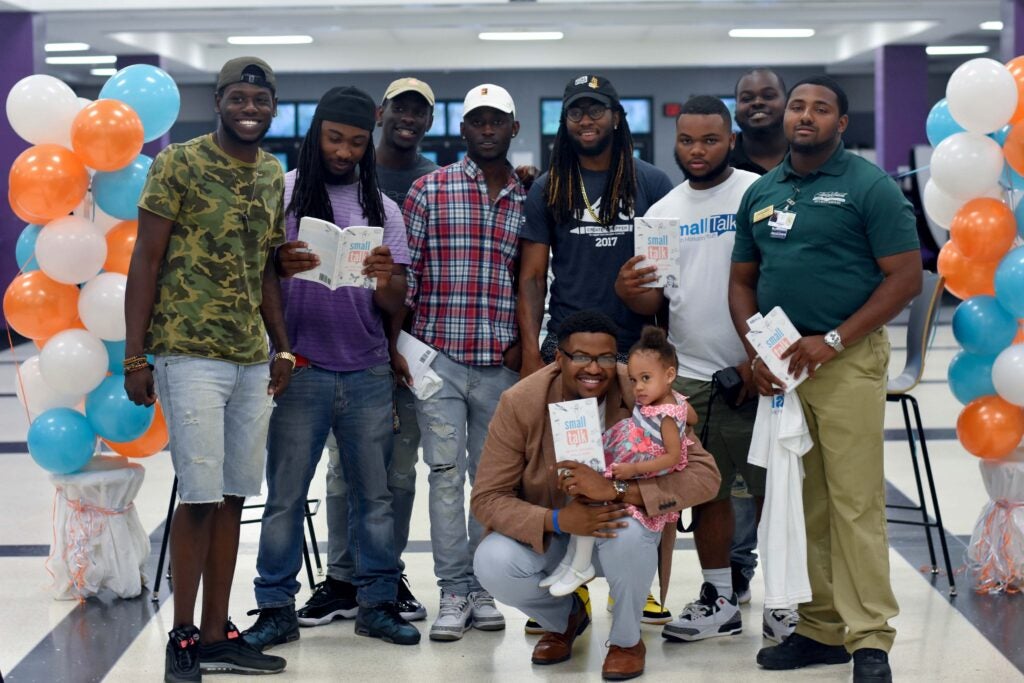

Jerome with childhood friends and his god-daughter at his Small Talk book signing in Charleston, SC.

As you’ve pointed out, in community conflict is inevitable. How do we attempt to repair it?

I’ve adopted a Buddhist approach that life is full of suffering, and harm is inevitable. With that, I shouldn’t fear the inevitable, it’s our job to find peace in our suffering. It’s just a matter of, How do I respond to harm in a healthy way? There’s a difference between harm and trauma. Trauma requires a deeper level and process for healing and a lot of community involvement. However, there are also daily harms that can collectively become traumatic if we don’t know how to handle them.

For me, meditation has been key. I recognized that sensations, thoughts, feelings, and emotions all arise in the same space of consciousness–out of thin air. With more mindfulness and understanding, we can make them all disappear, too. It’s about what you choose to fixate on. It takes empathy to put myself in others’ shoes, and to ponder why they may have caused the harm: Was the harm really something negative or just misplaced intentions? It’s also about centering what I can control, which is my reaction. I have to ask myself, What is this bringing up? Why is this triggering that?

There are some things that I’m very open about that happened in the past and things that I’m still nervous to talk about. I’ve realized the more I just accept and express that this happened, I can evolve to, Oh yeah, it happened; it’s no longer happening. And these experiences no longer have the same effects they once did.

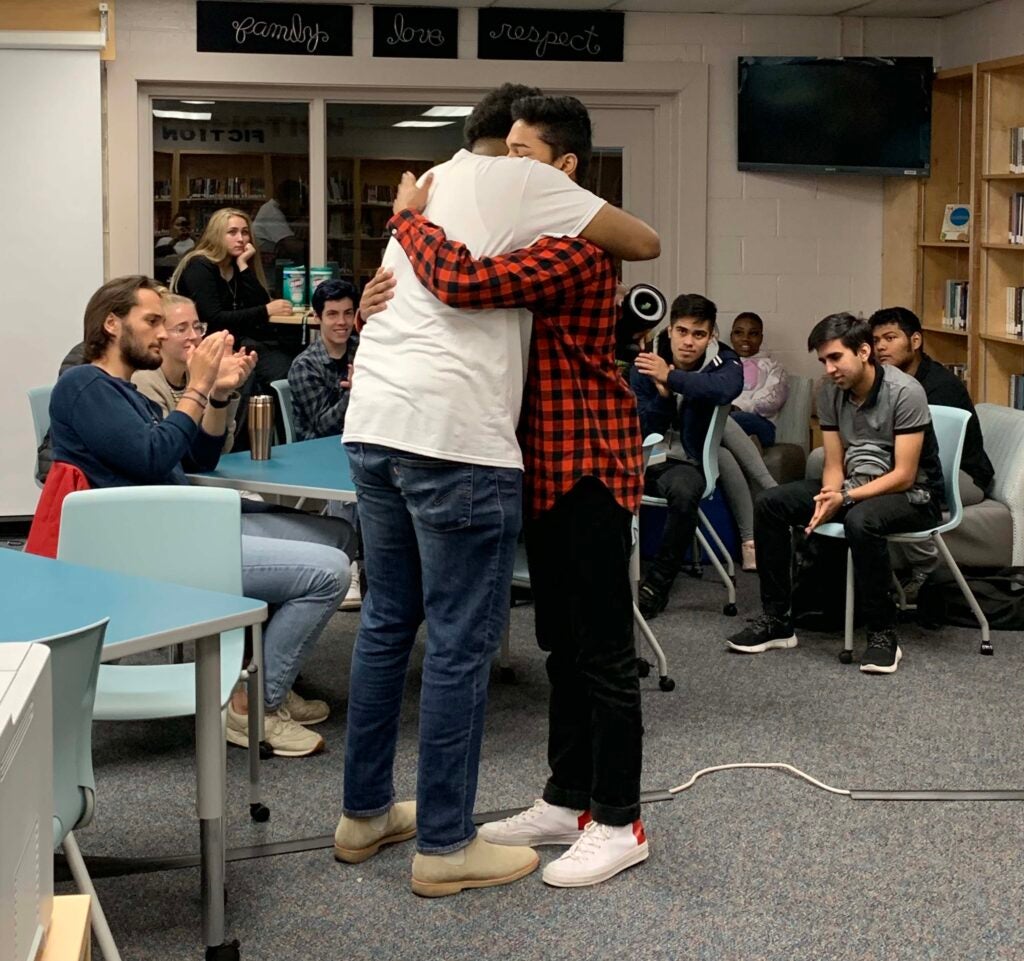

Jerome embraces a student after they shared their story as part of the Small Talk Storytelling Club.

How does a loving, faith-informed pedagogy shape your approach to cultivating a classroom environment where students feel comfortable learning and confident that they won’t be abandoned?

Collective commitment is where faith comes into play. Commitment isn’t because of who you are right now, what you bring to the table, your class, or your race. I’m committed to you because you are human. We have faith in this commitment and we’re gonna see this through. So I’ll call someone out because I’m committed to trying to help them grow–no matter how many times they need to hear the lesson. Eventually, they have no choice but to have faith in themselves. This same level of commitment to faith, love, and growth, is what I want at the center of pedagogy. This is especially important for Black students because there’s such a lack of love and commitment to them in so many other spaces, so we gotta give it to them in the classroom.

This interview is part of the Blackness & Faith series by Kawther Berhanu (C ‘19, MSFS ‘22).

Photos were provided by Jerome Smalls (MSB ‘19, G ‘23).