Reflection: The Kumari of Patan

By Nami Bolat, (C ’25)

We sped through the Patan Durbar Museum to arrive at our next destination in time: a visit with the Kumari of Patan.

The Kumari Devi we met that evening is the latest incarnation in a lineage of living avatars of the Newar People’s Shakta Dharma divinity Shri Taleju Bhavani, patron deity of the former kingdom, and now, state of Nepal. Taleju used to appear to advise kings in a physical form but disappeared following an attempted rape by one of them, appearing now in the form of a prepubescent girl who she chooses as her living embodiment. Interestingly, in Kathmandu, this Shakta Dharma divinity has always taken the form of a girl of the Buddha Dharma followers amongst the Newar People. The Kumari house we visited is, in fact, nestled in the corner of a courtyard of a Buddhist Vihara.

We removed our shoes, waited for a moment while the Kumari finished up her home-school lessons, and then were invited inside. Upon crossing the threshold, I suddenly became extremely aware of my body, my composure, and my presence, as well as of another indescribable presence, a subtle yet pressing one that I interpreted, in my own inadequate understanding of things, as that of the Divine Feminine that Shakta tradition reveres. I noticed the walls were painted pink and that several pairs of little girl’s shoes of various sizes rested against them. We clambered up a narrow staircase and were met with the mother of the Kumari who cleansed our hands before we passed through to the innermost room.

I can’t remember now if the floor of that room had cushions to sit on, which is curious because I spent most of my time there studying the ground. I was scared to look up, having been advised that the Kumari Devi would not smile or interact with us, and the indescribable presence I had felt crossing the threshold of her house only grew stronger as I took a hesitant seat towards the front of the room. I had no idea what to do with myself: I was stupefied and awestruck, feeling much smaller, weaker, and dumber than this five-year-old girl before me. I have cursed out priests who I felt gave me bad advice in the past during Confession, and left a poor nun sucking wind after me when I ran away from her for her tactless counseling: I’ve always been pretty unabashed in the face of religious authority. The marked difference between them and Kumari Devi was precisely the word authority (and perhaps, the established appreciation of supreme feminine power that exists in the former and not in Catholicism). Divinity was vested in her, arguably without her choice: she did not ask or strive for authority; Taleju endowed her with it. Seeing Dr. Sharan, director for Dharmic Life and Adjunct Professor in the College of Arts and Sciences, fully prostrate on the ground twice to receive the tika blessing, and knowing that for centuries Nepalese royalty and rulers have done the same before making any political act, only confirmed her power for me. At the time I only felt more reverence for her because of this fact, but as my classmates and I discussed later on, I, too, began to question how ethical such a duty placed on such young shoulders could be. We especially felt uneasy about the photo we took with her at the end of our visit. I vividly remember watching as Kumari Devi tucked a blue plastic bag behind her for the sake of a prettier photo, without being asked.

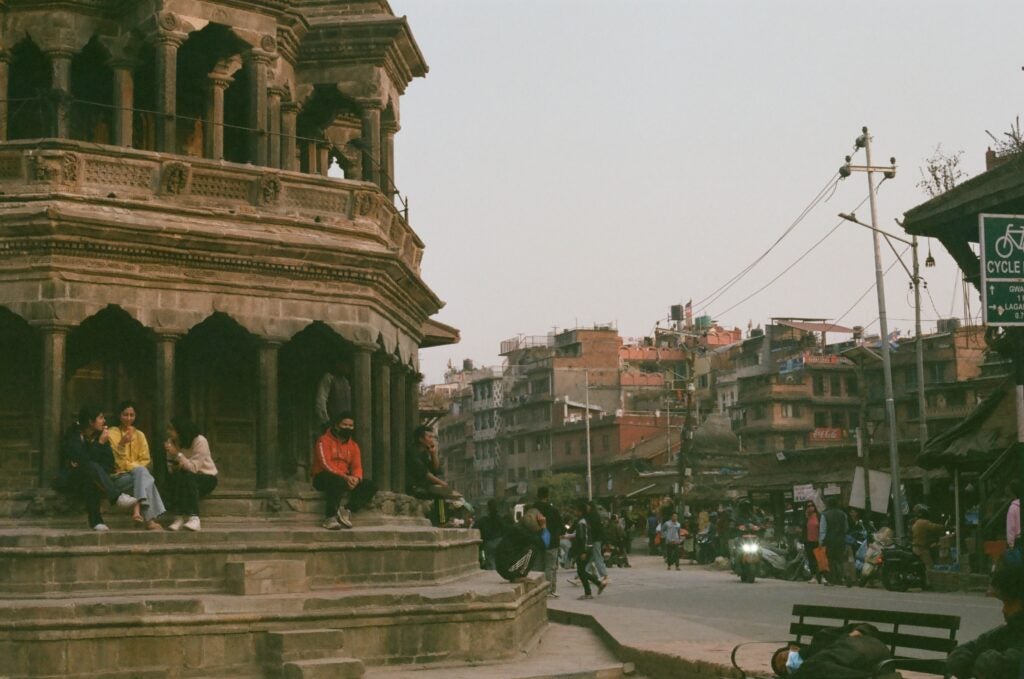

Patan Durbar, Kathmandu, a Vaisnava temple where students and trip leaders settled to debrief their encounter with the Kumari of Patan.

I felt incredibly rude as I received tika from her: I wish I could’ve thanked her appropriately, and told her that we appreciated her presence and power even if we didn’t fully understand the complexities of it all. I felt inadequately prepared to show adequate respect. That said, as we reflected a few nights later as a group, we learned that the visit was a surprise to Dr. Sharan; that he, too, felt all the turmoil we did when he first visited her a few years ago, that the photo was organized before we could intervene by the Sarala and the Kumari’s mother, and most importantly, of the reality of inter-worldview dialogue. In learning about other traditions in their authentic existences, there will necessarily be moments like these where one puts one’s foot in their mouth, one feels confused, overwhelmed, conflicted, and desperately afraid to not mess up, to not offend, to not be yet another ignorant Westerner intruding on a sacred space foreign to anything they’ve known. We must not be afraid to understand that there are concepts and practices we do not understand and appreciate nonetheless, taking every effort along the way to not deride the existence of these practitioners and of their traditions with our presence and Western perspectives.

Witnessing snippets of the Shakta, Shaiva, Vaishnava, Sanatana, Kirat, Vajrayana, and Theravada Buddhist Dharmic worldviews during this whirlwind trip left me with both a sense of fulfillment and continuing curiosity. However, I’m hesitant to adore the pieces of these traditions I witnessed only momentarily. To adore requires a deep understanding and a commitment to the preservation of these traditions that an unskilled and clumsy infatuation can destroy. Fascination is often destructive: Orientalism, the legacy of colonialism, inaccurate media portrayals of the Kumari tradition, and the active effects of postcolonialism and Christian conversion efforts are all testaments to that. To approach other worldviews with deference, and delicacy, with a commitment to preserve authenticity, is just part of what I have taken away from this indescribably insightful journey to Kathmandu.