Bearing Witness at the Border: A Look Inside the Kino Immersion Trip to Nogales

By: Jennon Bell Hoffmann

As the temperature of immigration and deportation rhetoric continues to climb, finding humanity and dignity in a crisis can feel like groping blindly in the dark. The Kino Border Initiative offers a comforting light. Rooted in Catholic teaching, the Kino Border Initiative (KBI) is a nonprofit organization that promotes humane, just, and workable migration through direct humanitarian assistance and holistic accompaniment of migrants. Through their Kino Immersion program, institutions, including Georgetown University, are invited to spend a week across the border in Nogales, Sonora, Mexico, to meet with migrants and asylum seekers, tour the resource center, and provide humanitarian services. Kimberly Mazyck (SFS’90), associate director of engagement of the Initiative on Catholic Social Thought and Public Life, recently participated in a Kino Immersion trip and agreed to share her experience.

Campus Ministry: Thanks for chatting with us, Kimberly. The Kino Immersion trip brought you to the forefront of the migrant experience. What expectations did you have about going on this trip?

The Georgetown group at KBI—photo credit Kristi Graves.

Kimberly Mazyck: I think there was trepidation before we went on the trip, because it does feel more charged. We had somebody in our group who had been a green card holder who had recently become a US citizen, and she was worried about crossing the border. We had another young woman whose parents crossed the border and had a family member die on her journey. We all brought something to the trip.

We had nine people, including me, from all across Georgetown—from Campus Ministry, a history professor, somebody who works on environmental sustainability and our Earth Commons program, as well as staff from the business school, the medical school, and the public safety office. The beauty of this mixed group is how we get all of these people in conversation about one topic. For me I have attempted to bring people together in conversation for most of my life.

CM: Let’s start with the itinerary. What were some of the things that you did while in Tucson, Arizona, and Nogales, Sonora, Mexico?

KM: The whole point of the Kino Immersion trip and its partnership with the Center for Social Justice and Mission & Ministry is to give people a real sense of what’s going on. Some of that time is spent at KBI, where you get to meet people who are at the shelter. But we also walked around Nogales, so we have a sense of what the city looks like. We saw the border from both sides, where people are coming through, and what they were dealing with.

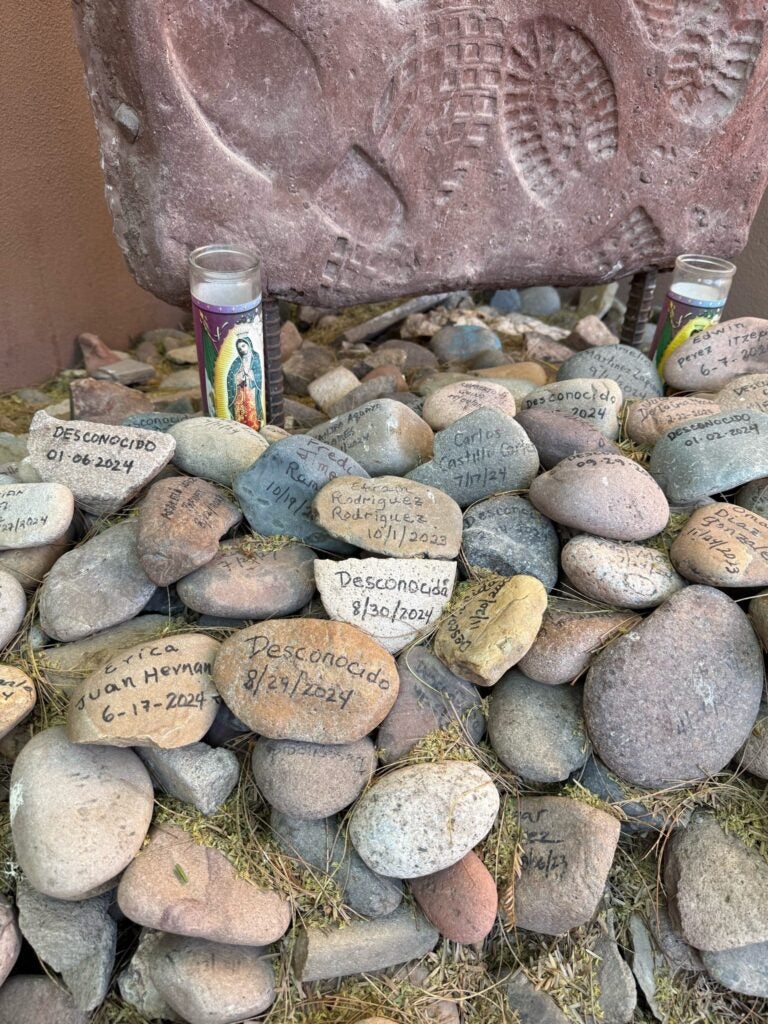

A rock garden outside a sanctuary church. Desconocido means “stranger” in Spanish—photo credit Steph Bautista.

We met so many people doing what they can. We met a woman who was part of the original sanctuary communities and churches that started in Tucson. We met with a member of the Sierra Club’s staff who studies the environmental issues of the migration processes; he was talking about what happens to put the wall in place, how dynamite is deployed to destroy the land in order to build the wall [affecting the landscape], and what happens to the animals and wildlife that die on either side of the wall because they can’t migrate or move, including birds that can’t fly up above it. We met a medical anthropologist who is working to reunite the remains of unidentified people who passed in the desert with their families. So we also get a picture of what’s happening to the environment, the communities, the ecosystem of people and animals, and the families. These are some pieces of a much larger, more complex discussion

CM: You spent time at the Migrant Outreach Center in Nogales to meet asylum seekers and migrants. Tell me about your experience.

KM: Where to begin? I want to tell you about one young man I met. His name is Alex, born in Oaxaca, 20 years old, and he comes over to me, saying that I look familiar to him. And we started talking, and then I noticed the Charleston tattoo across his arm. He says, “Oh, I’m from there,” and I tell him all my mom’s family is from Charleston, and my dad is from Mount Pleasant, across the river, and he asks, “Is your dad Geechee?” Most people use the term Gullah, but when you’re really from that part of the world and you were raised in a Black community, you use the term Geechee. [Gullah Geechee refers to members of coastal Black communities in the Carolinas and Georgia who are descendants of enslaved Africans.] And I looked at him, and I said, “Indeed.” Then his inflection, his voice, changes, like we know each other in this specific way, this ancestral way.

Migrating to Freedom reads graffiti on the border wall at Nogales, Sonora, Mexico—photo credit Ryan Zohar.

He tells me how he was brought across the border by his parents at a very young age, and all he knows is Charleston. He is soft-spoken and reminds me of my nephew, and by the end of the day, he’s calling me auntie and asking if I need anything. Such a beautiful individual, so kind, I know his heart is a good heart. He just wants to be in a community that he feels like he knows, and now he’s in a place that he’s never known, right? And he is more scared there [in Nogales] than he is in the States, and yet if he tries to cross again, he puts his life in jeopardy. I connect to this young man, so how am I not concerned about what happens to him? All I kept thinking is that these are people that we can be family with, want to connect with, sit with, and be a comfort, if nothing else. His story will stay with me forever, this young man trying to get back home.

Water left for migrants in the Sonoran Desert—photo credit Carolina Chernacov.

CM: It feels more important than ever to find dignity and humanity among the politics. How does your experience at KBI help you in your work at Georgetown in today’s climate?

KM: To answer that, I’m going to quote a priest. Father Emmanuel Williams, who’s in Montgomery, Alabama, was born and raised there, and has seen the Civil Rights Movement personally. What he said is, as Catholics and as Christians, “We are called to be political. We are not called to be partisan.” And that really spoke to me. If you’re a follower of Christ, if you think about the Gospel, Jesus is very clear about how we’re supposed to take care of each other and what it means to care for the most vulnerable. If a shepherd has a flock of sheep, the shepherd goes back to look for the one that is lost. And that one lost sheep is not any more important than the others, but at that inflection point, it is the most important one.

It’s easy for a lot of people to throw up their hands and say, “Well, I don’t want to get political,” and I think, No. Jesus told us we’re supposed to welcome the stranger. We’re supposed to take care of the man on the side of the road whom we do not know. And that’s our call if we believe in the common good, if we believe in being good stewards of the earth, that means we take care of each other. We do that with love and care, as Jesus took care of us, right? If I’m not doing that as best I can, I’m not living the Gospel truth.

Crosses in the Sonoran Desert—photo credit Carolina Chernacov.

CM: How are you sharing your experience with the Georgetown community?

KM: In terms of our Jesuit values, I think that we are building community within the larger Georgetown community. And when I think about my work with the Initiative for Catholic Social Thought and Public Life, it’s about engagement and creating these communities and opportunities that allow us to connect authentically and honestly. There isn’t a day that I don’t think about Alex, his story, his life—that’s a different connection. I can tell his story, I can strengthen the bonds of the community, I can bear witness, and most importantly, my connection to him.

In the fall, we are planning events so that we can bring what we saw, who we met, and what we learned. We keep doing what the Gospel calls us to do, as Jesus said. The simple answer is that we engage and empower each other to do the work. We can’t wait for someone else.

Kimberly Mazyck (SFS’90) is the Associate Director for Engagement of the Initiative on Catholic Social Thought and Public Life. Kimberly has served in key positions at Catholic Relief Services, Catholic Charities USA, and the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur East-West Province. She is a graduate of the Walsh School of Foreign Service with a degree in international relations and has a certificate in African Studies. She enjoys cooking and keeping in touch with her family.

Jennon Bell Hoffmann is a freelance writer and editor living in Chicago.